Chinese Calligraphy

The Art of Beautiful Handwriting

Calligraphy has been essential to Chinese culture since the first instances of Chinese writing over six thousand years ago. In those times, most calligraphy was done spontaneously on non-prepared stone surfaces, bones, and tortoise shells. The ancient artifacts remaining from that time are the earliest surviving documents in the Chinese writing system. Indeed, they represent a precious treasure trove of China’s heritage and are the embodiment of China’s traditional values.

The key to understanding early calligraphy is knowing that the strokes made by the writer are about expression, not about beauty. The emphasis was on precise control of the brush. Calligraphy was written in one movement starting from one end of a bone or shell and finishing at the other end.

Each letter in Chinese writing represents a picture story. In one stroke, different pictures combine to create meaning. In ancient Chinese writing, one could write fifty different characters with no repeated strokes, and each character could have a different meaning or concept.

Papermaking

For thousands of years, writing was preserved on materials not easily transportable. Clay tablets were the first to be used, after stones and bones, but they were limited in their portability. The next material used was papyrus, made from the reedy plant of the same name found in marshy areas. Papyrus disintegrated after a brief time, and its supply was too spindly to make high-quality writing sheets. The next material used was wax, which was appealing because it could be disposed of once its contents were no longer needed. Parchment eventually replaced wax for long-lasting use but required hundreds of animals to make the materials for one book.

It is unknown who first invented paper. Papermaking is not known to be the invention of any one particular culture. The Chinese likely invented the general technique of breaking cellulose fibers down and randomly weaving them together, but the specifics are obscure. Perhaps because remarkable stories work better with a central hero, Chinese schoolchildren are taught paper was invented in 105 CE by a eunuch in the Han court named Cai Lun. During the Han era, the demand for writing material surged when China’s first comprehensive national histories were produced, classic works that earlier dynasties had destroyed were reissued, and the first official version of Confucius’s teachings was recorded.

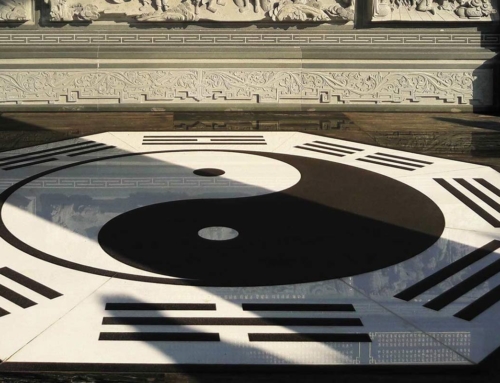

Confucius

The Chinese philosopher, poet, and politician Confucius (September 28, 551 BC – April 11, 479 BC) is traditionally considered by historians as the paragon of Chinese sages. The Chinese and other East Asian cultures continue to be influenced by Confucius’s teachings and philosophy even today.

China’s Five Classics and Four Books provided the foundation for civil examination and were considered the canon of Confucianism. The Five Classics are the Book of Odes, Book of Documents, Book of Changes, Book of Rites, and the Spring and Autumn Annals.

Written during the fifth century BCE, Confucius’s book Classic of Rites explains that masters of calligraphy pushed and pressed their brushes to the limit, seeking perfection. Further, it states that no master should ever submit anything but his best as he would not want to risk making others suffer through his inability to improve his own work. But why was calligraphy important in ancient China? Calligraphy provides a unique platform for a deeper understanding of Chinese culture and arts through its distinct form. In addition to embodying vital aspects of China’s intellectual and artistic heritage, it is a source of pride and pleasure for the Chinese.

The Importance of Calligraphy

One reason calligraphy was so important in China is that Chinese writing is complicated and difficult. Chinese characters are ideograms, with each character representing a word or even a phrase or proverb. There are about four hundred different Chinese characters, but they can be combined to represent tens of thousands of variations on the written page. Although there are distinct kinds of simplified Chinese characters now that did not exist in the past, the complexity of its writing system remains formidable.

In the past, calligraphy was even more important for the Chinese than it is today. It was more valuable than painting or sculpture and was viewed as the highest art form. Calligraphy was ranked alongside poetry in status and believed to be a means of self-expression and cultivation. Calligraphy requires a person to have both intelligence and taste. Intelligence meant that one needed to have the ability to express an opinion well, while taste required that one present it in an appropriate form. It was a sign of status. The better one’s handwriting, the higher the perceived social rank of that person. Calligraphy was a way of life:

- Nobles passed time doing calligraphy during court audiences.

- Officials used their spare time doing calligraphy on a desk with an inkstone in front of them just like people do now for leisure at home.

- Poets considered calligraphy practice as part of their literary pursuit.

Calligraphy evolved into one of the most important art forms in ancient China. The Chinese people had a profound respect for this art. They believed that calligraphy could combine a mood, feelings, and thoughts. Therefore, it showed the writer’s whole character.

There is an adage that “one word can reveal character,” meaning that one word choice can reveal one’s nature and feelings. The art of writing gives us some idea about how much thought a writer puts behind their words and how carefully the writer wrote out each character.

Throughout history, Chinese calligraphy has not just been a visual art, but it has also been an effective mode of communication. In the thriller novel Last Flower by Niklas Three, calligraphy plays a significant role.

Excerpt from “Last Flower: A Suspense Thriller Novel” by Niklas Three. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Zhang reread the message given to him by the Royal Harbin Hotel concierge. The handwritten dinner invitation came on a small, velvety, white scroll. Delivered in a red gift box and tied with gold, whisper-thin silk ribbon that he twirled through his fingers, the translucent paper was the perfect medium for the vertical columns of calligraphy letterforms. Each black ink logogram drawn with practiced grace, using traditional brushstroke characters, elevated the importance of every hanzi.

Unlike a hyperconnected text or email, the scroll was a quiet reflection, revealing a facet of a woman whom Zhang yearned to know. Her adept use of the Four Treasures of the Study—ink brush, inkstick, inkstone, and paper—expressed an unfussy elegance. Each thoughtful stroke conveyed an artist’s passion for the ancient pictographic and ideogram elements—her dynamic personality evident in the brush lines flowing with precision and flair.

He brought the stationery up to his nose. No hint of fragrance. Only the faint scent of ink and paper was discernible.

Calligraphy is not just the art of beautiful characters. It also embodies Chinese philosophy and cultural heritage handed down for thousands of years. In many ways, Chinese calligraphy is the perfect art form to follow in the footsteps of the artistic and architectural achievements of China’s dynasties. Today, calligraphy has become a popular form of expression, both highbrow and lowbrow, among Chinese who have rediscovered its significance and enjoy practicing it as an activity for improving their minds and expressing themselves.